Mt. Yarigatake

Chubusangaku National Park welcomes hikers to a majestic alpine landscape of towering peaks, snowy slopes, clear mountain streams, and diverse seasonal varieties of plant and animal life. The park offers a well-developed system of trails and mountain huts and challenging routes. It is home to 10 of Japan’s 21 peaks over 3,000 meters. The tallest is Mt. Oku-Hotakadake, the third-highest mountain in Japan at 3,190 meters, and the most recognizable is Mt. Yarigatake, whose 3,180-meter peak is said to resemble the Matterhorn. Mt. Tsubakuro, at 2,763 meters, is popular with novice hikers. Most of the summits are accessible, depending on one’s level of expertise, the time of year, and the weather conditions.

The following is a guide to hiking the mountains of the national park. Hikers are urged to check the latest trail and weather conditions thoroughly and gather as much information as possible before setting out. The local tourist associations are reliable sources of information, as are the local visitor centers. Hiking guides, some of them multilingual, can make the experience more enjoyable by sharing with you local customs, route information, safety hints and knowledge of the natural environment.

A Historic View: Climbing in the Birthplace of the “Japanese Alps”

Modern alpinism in Japan began in the Chubusangaku National Park with the arrival of European mountaineers in the Meiji era (1868–1912). But as in other regions of Japan, climbing in these mountains has its roots in the country’s indigenous religion, which deifies natural phenomena, including mountain peaks. Some areas had already become pilgrimage destinations or special sites where priests underwent strenuous ascetic training.

The first ascent of Mt. Yarigatake, the centerpiece of the Northern Alps, was made in 1828 by a Buddhist priest named Banryu. Besides ascetics, the mountains were also the domain of woodcutters and hunters, and one hunter named Kamijo Kamonji is now famed for guiding the first non-Japanese climber, William Gowland, to the peak of Mt. Yarigatake in 1877. Gowland was a British engineer and archaeologist, one of the many international experts invited to Japan to help with industrialization during the Meiji era. He was also an enthusiastic climber, and the first use of the term “the Japanese Alps” appears in his writings.

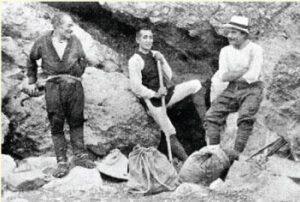

Walter Weston (right) with local guides Kamijo Kamonji (left) and Nemoto Seizo (center)

It was another British climber, a missionary named Walter Weston, who introduced Japan’s mountains to the world. After climbing several of the Northern Alps’ peaks, he wrote a book titled Mountaineering and Exploration in the Japanese Alps, which was published in London in 1896. Like his compatriot, he was guided by Kamonji, for whom he expressed high praise in the book.

Mountaineering became an increasingly popular activity as Europeans introduced alpine techniques and climbing gear into the country. The Japanese Alpine Club was founded in 1905, and the first university alpine club was founded at Keio University in 1915. The sport quickly spread all over the country, and peak after peak and route after route were conquered by enthusiastic climbers. Today, thanks to constant conservation efforts and the well-run system of trails and huts, there are innumerable destinations for hikers.

● Rocks on the trails are sometimes marked with a circle for the correct path or an X for a direction to avoid.

● When a dislodged rock can endanger people below, hikers call out “Raku!” an abbreviation of rakuseki (“falling rock”). Conveniently, raku is pronounced much like the word “rock.”

● The mountain slopes can be very steep, and going off-trail may not only damage the environment but also place you in danger.

● Listen to advice from mountain-hut staff, who are knowledgeable about their surroundings.

● Helmets are recommended for some of the more difficult sections.

● The weather can change very quickly in alpine locations. Be prepared and check forecasts often.

● A hiking registration form should be submitted at the trailhead or on the Internet. This is extremely important in case of emergencies.

● In the case of an accident, you may incur costs for searching and

rescuing. It is advisable to take out mountaineering insurance or travel accident insurance that covers hiking (it is possible to apply for this at a vending machine in Kamikochi)

● A navigation app is effective to prevent losing your way (there is a free English version). It is best to install it on your smartphone in advance, and download map data of your destination.

SUPPORTING HIKERS:

There are about 100 mountain huts in operation throughout Chubusangaku National Park, offering meals, accommodation, safety support, and information. Their origins may have been the small shelters built by loggers and hunters in the Edo period (1603–1867), but as mountaineering took off at the beginning of the twentieth century, huts began to focus on serving the needs of hikers. Some of the most famous have recently passed the 100-year mark: the Yarisawa Lodge opened in 1917, while Enzanso has been around since 1921. By the time the area was designated as a national park in 1934, most of today’s huts were already in operation.

As the numbers of hikers increased, the huts grew larger. Until the advent of helicopters, everything was carried up by hand, and anyone who has made the climb with a full backpack can well imagine how difficult this must have been. Now, thanks to helicopter deliveries and generators, guests can enjoy such offerings as draft beer, ice cream, and filling, hot meals. Drying rooms powered by large fans are a blessed relief for those who arrive soaked from a sudden mountain shower.

The huts have deep connections with their alpine locations. The operators and their employees are living encyclopedias who share their knowledge about the natural environment, trails, weather conditions, and much more. Most huts have been in the same family for generations, the operators’ ancestors having laid the trails that hikers still use. They take responsibility for maintenance, replacing washed-out bridges, restoring damaged paths, and cutting back foliage. They are often on the front lines when it comes to rescue operations, facilitating communications and, in some areas, supporting adjacent clinics that provide basic medical services.

OF YOUR STAY

Unlike most mountain lodges in Europe, many of Japan’s mountain huts are located close to the highest peaks. Operating accommodations in such extreme locales requires a lot of hard work and the cooperation of guests. Most Japanese visitors are already aware of the basic customs and schedules of the lodges, and visitors from overseas can ensure a smooth stay by learning in advance how things are done.

Some hikers hit the trails while it is still dark, and almost everyone leaves by 5:30 or 6:00 a.m. Since breakfasts need to be prepared and served, this means an even earlier start for the hut’s staff. Evening meals are served early too, usually at around 5:00 p.m. In order to prepare the correct number of meals and make room assignments, most huts expect hikers to arrive by 3:00 p.m. Arriving late creates additional work and problems for the staff.

Observing the customary arrival time may seem unnecessary to hikers who are renting a tent space and making their own meals, but latecomers will very likely find most good tent spots already occupied. The weather often deteriorates later in the day, and thick clouds and sudden rainstorms occur frequently.

Please keep in mind that another crucial reason for early check-in is the importance of daylight for any rescue operations. Conditions such as altitude sickness and hypothermia require a quick response.

Depending on the hut, the lights will be turned off at 8:00 or 9:00 p.m. and back on at 4:00 or 5:00 a.m. Many hikers are in bed even earlier than 8:00 p.m., so everyone tends to quieten down by then. It is also customary to pack early the night before so as not to wake others with noisy preparations.

Water is an extremely precious resource at high altitudes. The availability and quantity at the huts depend on how close they are to a water source, but all of them strive to conserve water. Some may even charge for its use, depending on the collection method.

Where possible, reservations should be made in advance. Not all mountain huts accept reservations, however, so carefully researching your options in advance is a must. If you have a reservation but decide to cancel your stay due to bad weather or for any other reason, be sure to inform the hut. The nonarrival of guests with reservations raises concerns about possible accidents on the trail.

Everyone is asked to carry out any garbage they generate. Toilet rules vary from hut to hut. Some require used toilet paper to be placed in a waste basket next to the toilet. Toilet waste is either carried out of the park or broken down through a waste-treatment system, both of which require considerable effort. While guests staying at the huts and campsites can use the toilets free of charge, others are asked to contribute about ¥100 per use.

The huts can get very crowded during peak season and on weekends. They never refuse anyone in need of shelter, so sharing a futon mattress is a possibility. If you fear becoming claustrophobic, avoid weekends and the peak seasons.

Most of the mountain huts do not accept credit cards, so be sure to bring cash for payment.

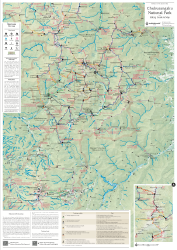

CLIMBING MAPS